Big Apple Sky Calendar: July, August, September 2025

In the 1990s, astronomy professor Joe Patterson wrote and illustrated a seasonal newsletter, in the style of an old-fashioned paper zine, of astronomical highlights visible from New York City. His affable style mixed wit and history with astronomy for a completely charming, largely undiscovered cult classic: Big Apple Astronomy. For Broadcast, Joe shares current issues of Big Apple Sky Calendar, the guide to sky viewing that used to conclude his seasonal newsletter. Steal a few moments of reprieve from the city’s mayhem to take in these sights. As Oscar Wilde said, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

—Janna Levin, editor-in-chief

July

July 1

Sunrise 5:27 am EDT

Sunset 8:33 pm EDT

On this and all later Tuesdays in July, the Amateur Astronomers Association will have night/twilight observing for the public from 7:00 to 9:30 from the High Line. Meet at the crossroads of Little West 12th and Washington Street. Watch the weather; rain or heavy clouds will likely mean a cancellation. Also, check the AAA and HighLine websites (both .org).

July 2

First quarter Moon.

July 3

Earth at aphelion. Today the Earth is 1.017 AU (95 million miles) from the Sun—as distant as it ever gets. Yet it's the hottest time of year for us borealites. The reason is that the Sun's local heating of the Earth depends not on distance, but on the angle of the noontime sun (now nearly overhead for us) and on the length of sunlight (now 15 hours).

July 4

Mercury at “easternmost elongation (26 degrees).” There’s no compelling reason to add “seeing Mercury” to your bucket list—except, perhaps, that it’s really difficult! Allegedly, even Copernicus never actually saw it. He was a “theoretician,” as we call them today, and must have relied upon the observations of others—especially 10–13 Arab astronomers, who did a very good job with it (and had much better skies). So, to one-up Copernicus, find a spot with an absolutely clear western horizon and look for three stars very low down, about 1 hour after sunset. The brightest and leftmost is Mercury; the other two are the Gemini twins Castor and Pollux.

Fortunately for us northerners, Mercury whips around very fast, and better opportunities will exist when the Sun is well to the south (mid-December of 2025 is good, when a nearby crescent Moon will point the way).

July 4 is also the traditional date for the appearance of the most famous supernova in history. What we know for sure is that in the early summer of the year 1054, a very bright “guest star” (the Chinese word) appeared suddenly, and was closely observed by Far Eastern astronomers (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean). It was described as “visible in daylight” for 23 days, and in the night sky for over a year. It must have been amazing to stargazers everywhere—but strangely enough, no definite record exists for its visibility in Europe or the Americas.

Today, the remnant of that explosion is still visible as the Crab Nebula, a small elliptical cloud of gas and dust. Virginia Trimble, an American astronomer famous for her quick wit and insightful astrophysics, found that the nebula is rapidly expanding, such that it must have originated from a single point around the year 1100 (and for once, she wasn't kidding). This proved that the Crab Nebula originated in the explosion of a tiny, faint star at its center, or perhaps the ancestor of that star. A few years later, it was found that this star is a pulsar—a solid star, made entirely of neutrons and spinning at a rate of 30 times a second.

This star is 6500 light years away—and if you do the math, you'll find that in the summer of 1054, this object was about as luminous as an entire galaxy. Holy mackerel! This was basically the beginning of modern stellar astrophysics. Two years later, the first black hole was discovered—and we were off and running.

But what's this “July 4” business? That's mainly a U.S. obsession. The ancient Chinese were exacting at dates, but not that exacting! (Or at least our knowledge of their dates is not that precise.) We do know three things that underlie the modern myth: (1) On the morning of July 5, 1054, as viewed from the western U.S., the waning crescent Moon was just northwest of the Crab Nebula's position; (2) several cave paintings and carvings from that region and era seem to show a round object (the supernova?) next to a crescent-shaped object of equal size (the Moon?); and (3) the Pueblo Indians of that era commonly made early-morning observations of the sky, perhaps to mark the seasons.

Despite this ultra-thin reed of evidence, few U.S. astronomy teachers can resist the retelling of the patriotic supernova story. I certainly can't.

Mosaic of the 1054 Crab Nebula.

Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsPictograph found in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, USA.

Photo: Greg WillisJuly 9

Birthday of John Archibald Wheeler in 1911. Wheeler was probably the most important American physicist of the twentieth century. (OK, Richard Feynman fans; you'll have your say later.) Wheeler became a teacher and mentor to nearly all American scientists working on general relativity, or Einstein's theory of gravity. He invented the terms “black hole,” “wormhole,” and “quantum foam.” And he came up with a single, short sentence that perfectly expresses the basic idea of Einstein's theory, and which replaces Newton's theory: “Space-time tells matter how to move, and matter tells space-time how to curve.”

July 10

Full Moon 3:38 pm EDT

July 13

From 1–4 pm, we’ll be hosting solar observing for the public at Pioneer Works and the same will be possible at Pier I (at the same time!)—the fishing pier west of Riverside Park, at 70th Street.

July 16

“Day of Trinity” in 1945—as it was called in Lansing Lamont’s famous book, to signify the first full test of a plutonium-implosion bomb. The test was designed by Kenneth Bainbridge (Oppenheimer for the overall leadership, Bainbridge for the test) who, after the blast, was reported to have said to Oppenheimer “we’re all bastards now.” There had been much debate among the scientists about the ethics of the bomb. Bainbridge ran a seminar for Harvard freshmen in the 1960s; I applied… and always wondered if I would have gotten in, had I shown my knowledge of the “actual” Trinity, acquired during prep school at a Benedictine monastery. (Nah, I decided that wouldn’t help… and didn’t get in.)

A second plutonium bomb was later dropped on Nagasaki. Planners were sure that the alternative “enriched uranium” (U-238) design would work—so they earmarked that, without ever testing it, for the first and most famous use of atomic weapons in warfare (Hiroshima, August 6).

In my opinion, the best of many books on these matters is Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb.

July 17

Last quarter Moon.

July 20

On this famous day in 1969, two astronauts landed and walked on the Moon. The story has been told a thousand times. Less well known is exactly what happened right after the quite dangerous landing. The original schedule called for the astronauts to catch some sleep before attempting the famous walk. But after all the excitement of the trip and peril of the landing, sleep was the last thing on their minds. Even though they had landed on… ahem... the Sea of Tranquility.

So NASA changed the plan and said “Okay, do the walk.” Then it was most-watched live event in television history: “One small step for a man...” Until, of course, the 2006 FIFA World Cup final between Italy and France, ending in a shoot-out. Now there was a reason to get excited!

Interesting side note: Of the six American flags planted by the six Apollo missions to the Moon, all are still standing (photographed by Lunar Orbiters) except the first, which was immediately and ingloriously blown down by the exhaust from the take-off rockets. (The take-off rockets were quickly re-designed to correct this egregious violation of flag etiquette.)

July 24

New Moon 2:11 pm EDT

July 26–27

Look west for “the old Moon in the New Moon’s arms” on these evenings. Mars can’t resist paying a close visit on the evening of the 28th. Any of these nights in late July are great for 11 pm–2 am viewing of the brightest regions of the Milky Way—the Scorpius-Sagittarius star cloud, and the Summer Triangle (Vega-Deneb-Altair).

July 24–27

Stellafane!

This is the oldest and most famous annual gathering of amateur astronomers in the nation. Beautiful night skies if clouds stay away. Events are spread over four days, so google “Stellafane” and take your pick. It's in the tiny town of Springfield, Vermont… which can present challenges in housing and dining. The deeply committed (there are plenty) camp out on Stellafane's hill.

July 31

Sunrise 5:50 am EDT

Sunset 8:14 pm EDT

August

August 1

Sunrise 5:52 am EDT

Sunset 8:11 pm EDT

First quarter Moon—directly south at sunset. Really good time for telescopic viewing of the Moon’s most cratered regions.

August 3

The Moon passes very close to the bright red-supergiant star Antares tonight.

August 1–5

On any clear morning in early August, look for Orion rising low in the east about an hour before dawn. “Ghost of the shimmering summer dawn / King of the winter nights!” It’s my personal favorite season-defining sight in the sky.

August 7–14

Jupiter and Venus, king and queen of planets, stage a little dance low in the eastern morning sky this week. From August 7–10, Venus is just above Jupiter. But Venus, brighter and moving faster, passes Jupiter on August 11. The waning crescent Moon, moving still faster of course, passes the pair on August 19.

August 9

Full Moon 3:56 am EDT

August 10

Today, the Sun enters the constellation Leo. But it entered the astrological sign of Leo 20 days ago, on July 22. What's up with that? Part of this shift arises from minor tinkering of constellation boundaries by humans… but most of it is courtesy of the Earth's wobbling axis. In addition to its better-known motions (spin, orbit), the Earth has a third and very subtle motion—the slow precession of its axis, like a wobbling top. The axis now points towards Ursa Minor—in fact, almost exactly towards the medium-bright star Polaris, which we therefore call The North Star. But the axis slowly wobbles around the sky, and this causes the seasons to slowly lose touch with the constellations. Our calendar, however, pays attention to seasons, not constellations. So most people who think they're “Leos” are actually “Cancers.” I don't know what the implications are… but it doesn't sound good.

August 11–12

All night, the Earth's journey takes it through a diffuse stream of cosmic dust particles which were once shed by Comet Tempel-Tuttle (named after that comet's discoverers). When a comet sheds matter (dust particles), it doesn't really go anywhere—it just wanders off ever so slightly, continuing roughly in the same orbit for thousands of years. Those little dust particles are like the odor particles emitted by humans and detected by bloodhounds. Except that the Earth, unlike bloodhounds, must follow the law of gravity—and only encounters that stream when its orbit intersects the stream's orbit, in early August.

The Earth encounters the dense part of that stream every August 12, and many of the dust particles fall to Earth with a streak of light—a meteor. The meteors appear all over the sky… but if you trace back the streaks of light, they all appear to be coming from the constellation Perseus. Hence the name: the Perseid meteor shower. It’s the most reliable of the annual showers, and many stargazers plan summer outings to watch the Perseids. Unfortunately for us in 2025, it nearly coincides with the Full Moon, whose brilliant light will wash out all but the brightest of meteors.

August 16

Last quarter Moon.

August 18

On this day in 1868, one of the most historically important solar eclipses was observed in Thailand. During totality, several teams of astronomers—mainly British—took spectra and photographs of the Sun’s lower and upper atmosphere (the “corona”). They found a yellow emission line which occurred at a wavelength never seen before on Earth—so they named it “helium,” after the Greek name for the Sun. That was the beginning of helium’s glorious history. Today we recognize it as comprising approximately 25% of the Universe. Essentially all the Earth’s atmospheric helium has escaped—because helium is so light that Earth’s feeble gravity can’t hang onto it. Mendeleev’s periodic table, for example, has no element of atomic number two. Nor does helium combine with any other element—it’s a “noble gas,” to use the lingo. Our only source of helium is through the radioactive decay of heavy elements mined from Earth’s interior (e.g., uranium). That’s why we have any helium at all (for balloons, cryogenic experiments, etc.).

August 19–20

On these mornings, the waning crescent Moon charges past the Venus–Jupiter conjunction in the eastern sky.

August 21

This morning will feature a very good apparition of the International Space Station (ISS) for NYC observers. It will suddenly appear nearly overhead (emerging from the Earth’s unseen shadow) at exactly 4:26 am and move rapidly eastward, disappearing (re-entering the unseen shadow) low in the east two minutes later. It’ll be very bright—brighter than any star. Worth an effort to see, especially with the Venus-Jupiter conjunction costarring near the eastern horizon.

August 21

This was the date of the “Great American Eclipse” in 2017. The moon's shadow swept from the Oregon coast, across the Rockies and the Midwest, before finally heading out to sea near Charleston, South Carolina. Nearly all observers enjoyed beautiful weather and got to witness this once-in-a-lifetime spectacle.

If you spend your life rooted to one spot on Earth, you'll have to wait about 400 years between total solar eclipses—and that's assuming no cloudy days! But NYC is in the midst of a streak: four between 1925 and 2020. For the 1925 event (totality occurred above 96th Street in Manhattan), The New York Times scolded the Columbia University astronomers in headlines for getting the time wrong by four seconds. Maybe the Times was miffed because totality didn’t include them.

If you’re inclined to think about future total solars, here are the ones to consider:

2026 August 12: Greenland, Iceland, Spain, or some ship in the North Atlantic

2027 August 2*: Spain, most of North Africa, Saudi Arabia

2028 July 22: Australia, New Zealand

2030 November 25: South Africa, Australia

August 23

New Moon 2:06 am EDT

August 25

On this day in 1835, the first installment of the most successful moon hoax of all time was published in The New York Sun—revealing the amazing discoveries of John Herschel with “an immense telescope” newly installed at the Cape of Good Hope. The author, Richard Locke, reported that Herschel had found the Moon with rivers, abundant wildlife, and humanoids with wings. There were no photographs to prove it (hey, photography was still a decade away), but there were some great, great drawings.

Locke was no stranger to hoaxes, and hoaxes were not rare in the nineteenth-century literary world. They were great for selling newspapers. Most newspapers at the time were sold on the street, with barkers excitedly announcing the juiciest story. This series (there were five more issues) really energized the popularity of The New York Sun. Unfortunately for science, fate intervened. The final issue reported that the telescope was so immense, humans couldn't handle it. Someone trained it on the Sun a week later, in search of yet more amazing discoveries—and wouldn't you know it, that burned down the whole observatory. No more discoveries to report. Not even a trace of the telescope for party-pooping investigative reporters to examine.

Edgar Allan Poe was plenty jealous about this. He had earlier published a very similar story, featuring a traveler flying to the Moon in a balloon and finding similar goings-on. But as a story, with obvious satire and no pretense of accuracy, it just didn't have the impact of a real astronomical discovery.

Vignettes of creatures supposedly seen on the Moon, 1835.

Courtesy of the British MuseumIllustration of the Great Moon Hoax, 1835.

Courtesy of the Library of CongressAugust 27

On this day in 1883, the greatest volcanic explosion in history occurred: Krakatoa! The blast was heard by humans 3,000 miles away, and the pressure wave travelled around the Earth three times before finally becoming undetectable by barographs. The explosion was 10,000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb. Volcanic dust was blasted into the upper atmosphere, where it lingered for many months—lowering the Earth's average temperature by about one degree. Krakatoa is part of the “Ring of Fire,” the huge region where the Pacific Plate crashes into plates to its west (Japan, Southeast Asia) and east (California, the Andes, etc.). Mount Saint Helens (1980) and Pinatubo (1991) are other members.

August 29

The exact 50th anniversary of Nova Cygni 1975, one of the most famous “classical novae” in history. I received a phone call on that night in 1975, directing me to go out and look up… and behold, I saw an “extra star” in the famous Summer Triangle. (Sometimes it pays to know your constellations.) It erupted from a blank spot in prior sky photographs, leading to speculation that it was the long-awaited supernova (none had been seen in our galaxy since 1604). And it was my first day of graduate school at the University of Texas. A few weeks later, I received telescope time at Texas’s McDonald Observatory and found a little 3.3 hour wiggle in the light curve. I wrote a research paper about it, followed by several others during my years there. That wiggle turned out to be closer to an “ordinary” nova (an exploding white dwarf), but with the twist that the white dwarf was strongly magnetic.

Nova Cyg was first seen by observers in Japan, then Korea, China, Russia, and others as sunset occurred progressively later at those longitudes. By sunset in Texas, at least 2,000 independent discoveries must have been made (phone calls don’t count, of course!). Sitting there as an intruder in the Summer Triangle, it was hard to miss.

August 30

Birthday of Sir Ernest Rutherford in 1871. By firing alpha-rays (helium nuclei) at gold atoms, Rutherford became famous for revealing the tiny size of the nucleus of all atoms… and for his terrible singing, as he roamed the famed Cavendish Laboratory trying to inspire students with “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

August 31

Sunrise 6:22 am EDT

Sunset 7:28 pm EDT

First quarter Moon

September

September 1

Sunrise 6:23 am EDT

Sunset 7:28 pm EDT

Today, the equation of time is zero. Nowadays, probably 90 percent of astronomy PhD's would have no idea what this even means. But for most of the last thousand years, it would have been elementary to all astronomers, clockmakers, ship captains, navigators, and many ordinary citizens. Why? Because, historically, the only really practical and accurate clock in the natural world (larger than atoms/molecules!) is the Sun. Shadows—and more precisely sundials—were the way you could measure time.

Here's how it goes (in the Northern Hemisphere). Roughly speaking, the Sun is directly south, and casts a shadow directly north, at local noon every day. But there are two reasons why this is not exactly true. (1) The Sun moves in an elliptical orbit—fastest when it's near the Earth (in January), slowest when it's most distant (in July). (2) It moves in a plane different from the Earth's equator (by 23 degrees). Sundial-makers, ancient and modern, usually capture these two small corrections (up to 20 minutes) by etching a little wavy curve called the equation of time. But on this day, the corrections are zero, and the Sun is precisely south at noon!

Well, not quite. More precisely, local noon. But in 1883, the U.S. legislated “Standard Time,” which meant that everybody within approximately 500 miles east or west of a standard longitude (which for us is 75 degrees east of Greenwich, England—roughly Philadelphia) must be on that time. NYC is slightly east of Philadelphia, so the Sun is directly south (“crosses our meridian,” to use the lingo) slightly sooner—at 11:56 am. Check out your shadow today—that's when it points exactly north. (But remember, there's another purely legislated correction—Daylight Saving Time—to which the Sun and its shadows are indifferent. So, it’s 12:56 pm EDT.)

Many things labeled as sundials are simply vertical or inclined sticks with a horizontal scale for the shadow. Many are sold as small works of art for your garden. These lack all precision, but after looking at the selections online, they're number one on my birthday wish list. I'd love to hear about large sundials still up and unmolested in the NYC area.

And on this date in 1859, Richard Carrington and Richard Hodgson independently observed a huge solar flare—probably the hugest in history. If such a thing happened today, it would probably ground all airplanes for several days (because the cosmic-rays at altitude would be very dangerous… and forget about communications). On the positive side, there would be great auroras—seen in 1859 as far south as the Caribbean. It’s now known as “the Carrington event,” because it was manifest in so many ways.

September 3

Birthday of Carl Anderson in 1906. He discovered the positron—a positively charged electron. This was the first hint of antimatter, but we now know that antimatter is plentifully produced in many astrophysical and particle-physics settings. It’s elusive because, as soon as it’s produced, antimatter looks around for matter to annihilate—producing a photon with energy 2mc².

September 7

Full Moon 2:09 pm EDT

A total lunar eclipse occurs at this time today. Unfortunately for us, it occurs near mid-day in all of the Americas, when the Moon is far below our horizon. It’s basically an eclipse for anyone within 2,000 miles east or west of India.

September 14

Last quarter Moon.

September 16

The Moon is just north of Jupiter in this morning’s sky.

September 17

On this date in 1882, the brightest comet of the last 500 years reached perihelion (its closest approach to the Sun). It was 50 times brighter than the Full Moon, and could easily be seen in the daytime sky. Unlike practically all comets, it never received a proper name, other than “The Great Comet of 1882.” Like most Sun-grazing comets, it broke into pieces after it passed perihelion. No matter how spectacular, all comets are objects of very small mass; and if they get too close to the Sun, the tidal forces can rip them apart.

Later studies of its orbit suggested that this was just a fragment of a yet-bigger comet in the year 1106—and the famous comet of 1965 (Ikeya-Seki, my first comet) may have been another fragment of the 1882 comet.

September 19

In this morning’s sky, low in the east, the waning crescent Moon stands next to Venus.

September 20

On this day in 1956, the U.S. Army launched a “Jupiter C” rocket which reached a then-record 700 miles altitude, and could have easily reached orbital velocity if the fourth stage had ignited. However, the War Department (NASA didn't exist yet) had ordered that the fourth stage be a dummy—lest the Army actually launch a satellite and thereby embarrass the Navy, to whom the satellite mission had been assigned. Over the next year, the Navy's Project Vanguard met with a series of failures, and finally came the October 1957 Russian Sputnik launch, which embarrassed (and scared) practically everyone in the U.S. government. A few days later, the Army's Wernher von Braun got the call—"Hey, do you guys happen to have another Jupiter rocket lying around?”—which led to the January 1958 launch of Explorer I, the U.S.’s first satellite.

September 21

New Moon 3:53 pm EDT—and a partial solar eclipse.

The Moon’s orbital plane is inclined by approximately five degrees from that of the Sun, so every New Moon is within five degrees of causing a solar eclipse. This month’s New Moon is about half a degree away from the Sun’s orbital plane (called the ecliptic, for precisely that reason), so the resultant partial solar eclipse is only barely visible in New Zealand and Antarctica. Everywhere else, the solar shadow misses the Earth altogether.

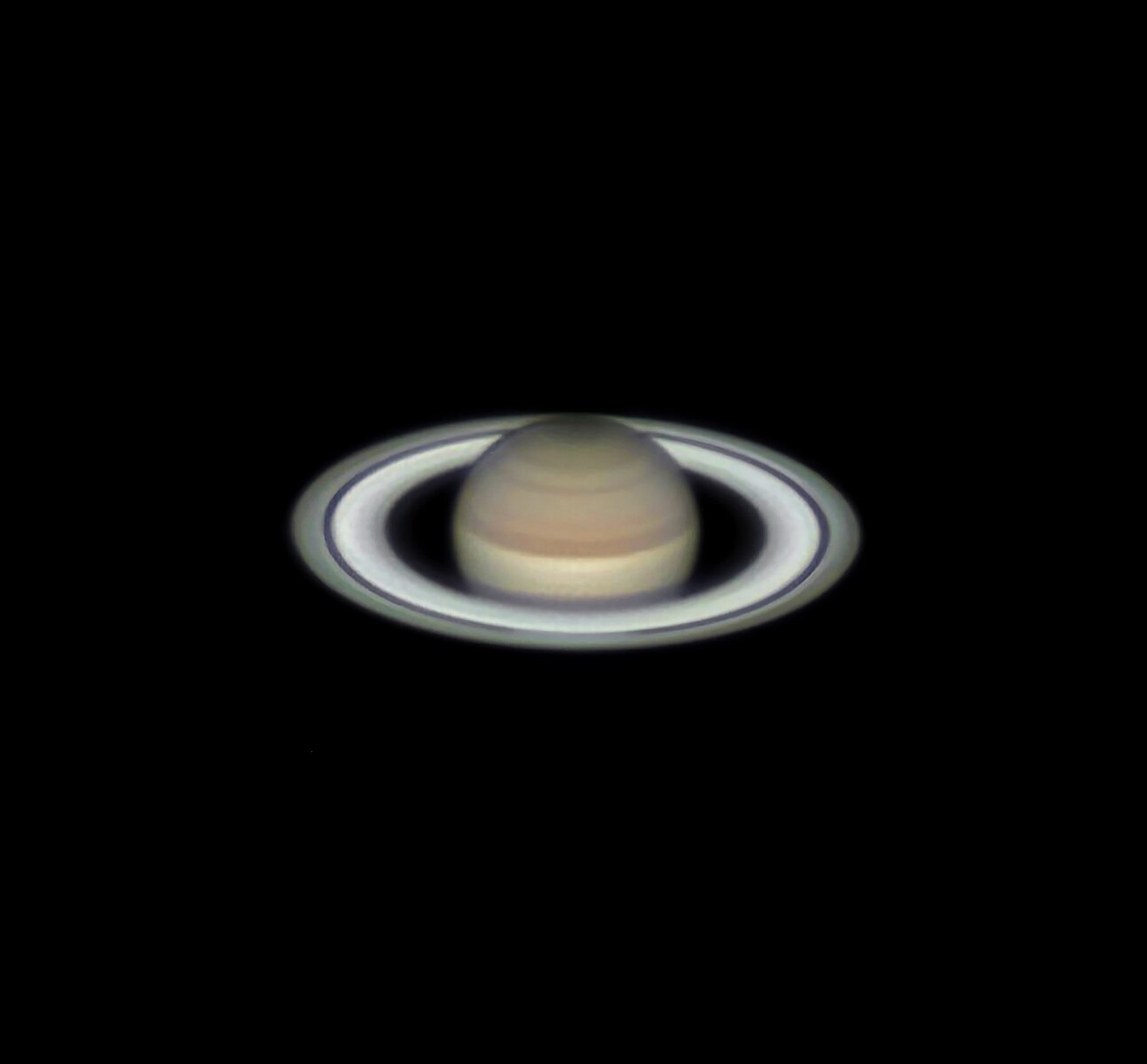

Saturn is also at opposition. This means it crosses the meridian at midnight. This should normally be ideal for observing Saturn. But the rings are very nearly edge-on this year (in March they were exactly edge-on, but the Earth’s motion has carried us around to where we can get a slim peek at them)

September 22

The Fall equinox occurs at 2:19 pm EDT (or the September equinox, just to be fair to our southern-hemisphere colleagues). Eggs will stand on end today.

Just kidding. It'll be a normal day for eggs. But on this date, day and night are 12 hours long, all over the Earth—except at the precise North and South Poles (where the Sun is now exactly on the horizon, rolling 360 degrees around as the “day” proceeds). I saw this once, by total accident, when I was flying over the North Pole at age 13 on equinox day. Sure enough, the Sun never fully rose or set, but just rolled along the horizon during the approximate six hours “over the Pole.” Of course, neither I nor my parents had any idea why!

I do remember, though, that precisely when the pilot said “we’re now over the North Pole,” I looked down and saw nothing but blue water. In part this must have been due to the date (end of the six-month summer day), but in part also due to the pilot’s imprecision. (I’ve since learned that the ice never entirely disappears at the exact pole).

September 25

Day and night are precisely equal, at 40 degrees north—if, for sticklers, you account for atmospheric refraction and the slightly nonspheric shape of the Earth. My guess is that zero astronomy professors are sticklers to that degree.

September 29

First quarter Moon.

September 30

Sunrise 6:51 am EDT

Sunset 6:39 pm EDT ♦

Subscribe to Broadcast